- Home

- Judith Hale Everett

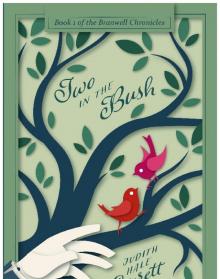

Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush Read online

Two in the Bush © 2020 Judith Hale Everett

Cover design © Rachel Allen Everett

Published by Evershire Publishing, Springville, Utah

ISBN 978-1-7360675-1-2

Two in the Bush is a work of fiction and sprang entirely from the author's imagination; all names, characters, places and incidents are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual people (living or dead), places or events, is nothing more than chance.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the author. In other words, thank you for enjoying this work, but please respect the author's exclusive right to benefit therefrom.

To Joe

my knight in shining armor

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

In vain did the countryside of Hertfordshire burst forth in all the glory of autumn, gilding the rolling hills with fire and ennobling its manors and cottages, castles and ruins alike with golden hue. Sir Joshua Stiles merely urged his pair to a canter—unmoved by the charm of a lane overhung by ancient beeches, a valley of charmingly walled fields, and a burbling stream forded by a neat stone bridge—while inwardly cursing his own perverseness in accepting Amelia’s tiresome commission.

Indeed, he had suspected the existence of a plot from the moment she had, with studied nonchalance, presented her request to him. He should immediately have demurred, but if he felt he owed nothing to the rest of the female race, he did owe brotherly obligation to her, so he had merely signaled his disapprobation with a raised eyebrow.

She had been moved to protest. “I felt sure you should have no objection to obliging me, Joshua,” she had said, “for Branwell Cottage is a mere step from Aylesbury, you know, and it would be such a kindness to my poor friend, and such a favor to me!”

With this last point, he had been in full agreement, and condescended to say so. “I’ve no doubt of it, my dear, but—you will pardon my curiosity—has something occurred to disrupt the Mail?”

“What can you mean?” she had cried, blinking. “No, of course not, but it would greatly relieve my mind to know the letter had been delivered into her hands, and not misplaced somewhere along the way, the post being as it is nowadays, what with all one hears of footpads and highwaymen, and young bucks tooling the coach! Oh! I have spasms at the very prospect!”

“Very disturbing, indeed,” he agreed drily, knowing full well that, thanks to Mr. McAdam, the roadways had never been safer than in the present day. “One wonders how anyone finds courage to repose their trust in the Royal Mail at all.”

“To be sure!” she had said, gratified at his quick comprehension. “And that is why I find it most providential that your journey takes you so near Branwell, for Cammerby may give you the direction, and I declare you shall not grudge the extra distance one bit, with the country being so lovely this time of year, though it has been so wet, and a jaunt of a few miles off your path will break up the tedium of your drive.”

As she had hoped, Sir Joshua’s sense of duty did not disappoint, and with a long-suffering sigh, he had accepted the commission. But if Amelia had had any notion of what was to befall him, she should have instantly repented her request, and forfeited her letter to the caprice of the Mail, and her plan—which indeed she had hatched—to a more favorable future.

The two days preceding Sir Joshua’s journey had brought torrential rains, but as this morning had dawned as bright and as warm as could be possible—given that it was October, and given that it had been the dreariest and coldest year for weather he could remember—he had set forth in his curricle, letter in hand, with no more presentiment of evil than that the detour necessitated by his brotherly kindness would in all likelihood make him late for a nuncheon appointment with an old schoolfellow in Aylesbury.

Indeed, the condition of the King’s highway gave him no cause for concern all the way to Chesham, but after Berkhamsted, where he turned out of his way and into the unknown territory described to him by his brother-in-law, the state of the roads rapidly deteriorated, becoming so horridly muddy in places as to try even the spirits of his matched bays, whose mincing progress ill-befitted their magnificence, and that of the well-sprung equipage they led. Sir Joshua, his eye on the rapidly moving sun overhead, at last resorted to a detour on a likely road that ran toward rising ground, only to be rewarded by a bone-rattling ride over deep, rocky ruts.

Another detour proved more propitious, however, and he made good time over several miles of even roads, until his path was suddenly blocked by a group of milk cows who apparently considered the right-of-way to be their own. The cowherd, having the effrontery to grin in response to Sir Joshua’s civil desire that he bestir himself, merely shooed his charges forward along the road, rather than to one side or the other, and the cows, apparently sensing no urgency, either from their master’s prodding or from Sir Joshua’s blistering glare, consumed nearly a quarter of an hour of precious daylight in their progress.

The continuation of a smooth road after this obstacle served to stem the tide of Sir Joshua’s deprecatory thoughts of sisters who could do nothing but fuddle the well-ordered lives of their brothers with frivolous errands, but just as he had begun to trust that he might join his friend in Aylesbury in time for dinner, he was obliged to pull to the side of the road to attend to a lame leader. The execution of this simple task so aggravated his temper that he jobbed at the horses’ mouths when they were set to, and his subsequent self-reproach quickly fanned into hot recrimination against all localities whose inadequacy had precluded their establishing a turnpike trust—a conviction that was unimproved by the sudden commencement of a succession of pot-holes on the tightly hedge-lined road.

When, at long last, an obliging side road appeared, he set his pair at a gallop along it, keeping an eagle eye open for the signposts Lord Cammerby had described, until a dip and a turn brought him face to face with a mass of bleating sheep. At sight of this bucolic prospect, Sir Joshua—though at no time possessed of an aversion either to sheep or to their masters—was seized by an overwhelming desire to wring the shepherd’s neck with his bare hands. This violence of feeling exercised such an exhilarating effect upon him that, snapping his reins, he plowed without ceremony through the startled animals, parting them as effectively as Moses had the Red Sea, and the curricle bowled along at a rate which should have been purgative to his anger, had it not, less than a mile down the lane, come abruptly upon a stationary wagon angling across the road.

Sir Joshua was not, in general, a man given to extremes of emotion. Taciturn by nature, even his wit was so dry as to burst upon the unsuspecting with startling effect. But the loss of his young wife ten years earlier had dealt him a stunning blow, from which he had never quite rec

overed, and though the impenetrable shadow of grief had at last receded, it had left behind a veneer of cynicism that was as deceptive as it was brittle. While his male associates were apt to turn a blind eye to this alteration, his sister, with the insight unique to the female sex, ever more devoutly hoped that something should occur to reanimate his tenderer feelings, and return him to himself before it was too late.

In fact, she had pinned all her hopes for his future felicity upon the success of this journey, for his unhappy circumstances were a problem which continually exercised her mind. This proposed visit to an old schoolfellow had coincided so wonderfully with the necessity of a timely reply to her dear friend that she was persuaded the occurrence was nothing less than the harbinger of his redemption, and had instantly set her ingenuity to work.

Had she been privileged to witness the effect of her labors she may well have lost all hope. For, coming upon the wagon, Sir Joshua was forced to pull up his team so sharply that they sat halfway on their haunches, and as they danced to a standstill, he surveyed the scene before him in formidable silence. The driver of the errant vehicle was nowhere to be seen and, unable to perceive immediately why the wagon was thus positioned, he swung down from his curricle, striding forward through the mud and challenging the quiet countryside, “What dashed nonsense is this?”

A figure popped up from behind the wagon near the front wheel, and Sir Joshua’s angry step faltered. It seemed that the owner had not, in fact, abandoned the vehicle, and, to complicate matters, was a female. Unfortunately for the lady, these facts did little to soothe his temper, and he barked, “Do you not realize you are blocking the entire roadway?”

The lady’s already heated countenance blushed hotter, and she brushed several wayward strands of hair from her cheeks. “Of course, I realize it, sir,” she said with some asperity, gesturing impatiently to the wagon. “How could I not?”

This agreement of temper hardly mollified his own, and he retorted, “And what, other than hiding behind the wheel, do you propose to do about it?”

“I was not hiding, sir!” she cried, her eyes flashing, but she closed her lips with a visible effort at civility before continuing, “I have been trying my utmost to correct it, but the wagon will turn the wrong way, no matter how I back the horse, and now the front wheel is mired!”

Even his jaundiced eye could see the justice in her predicament, but it obstinately searched for fault as he gazed narrowly at the lady. She was a mature woman, probably near in age to himself, and though she gave an impression of elegance, she was not at all attractive at the moment, with her shabby coat and skirts inches deep in dirt, and her dark hair escaping from its bonnet and whisping wildly about a perspiring and flushed countenance.

His better nature—which his sister hoped but could not be sure he still possessed—stirred with Herculean effort and, aided partly by his innate sense of duty and partly by the fact that any more delay should cost him his dinner, moved him to wrap the reins on an obliging branch, tossing his whip on the seat of the curricle. “Stand aside, ma’am," he said curtly. "I will see what can be done.”

The lady, her head high, looked for a moment as though she would demur, but he shouldered himself between her and the wagon, leaving her little other choice than to move out of the way as he bent to inspect the wheel. It was indeed mired, halfway up to the axle, but his inspection was arrested by the sight of several stones thrust into the mud before the wheel, and he raised his head to cast a more appraising glance at his companion.

“Did you place these stones here?” he asked gruffly.

Her blue eyes regarded him dispassionately. “Certainly I did, sir. You cannot believe they moved there of their own accord.”

He grunted at this, slightly appeased by this evidence of her intelligence—and of her determination to help herself, which he had always approved of in a female—and went to the cob’s head. Taking the bridle firmly, he urged the animal forward, and through the physical effort of working with the horse and the novel and ennobling awareness that he was providing help to one in need, the brooding thundercloud about him gradually eased. By the time the wheel came free, Sir Joshua’s patience was, if not wholly restored, at least once more in evidence, enabling him to endure the necessary tedium of maneuvering the cob forward and backward at the optimum angle to the wagon, several times, while the vehicle’s owner, her affronted air forgotten in observing the skill with which he brought the cart into alignment, tried without much success to tuck her loose hair back into her bonnet.

When the wagon had been righted, she stretched out her hand to him in goodwill. “Masterfully done, sir! Though I am persuaded I should have succeeded by and by on my own, I cannot grudge your able assistance. You have my thanks.”

“Pray do not regard it, ma’am,” Sir Joshua responded, irked by this somewhat back-handed gratitude. “It’s a devil of a place to lose control of your vehicle.”

The civility stiffened on her face. “One does not always have the good fortune to choose when and where one loses control, sir.”

“May I inquire, ma’am, or would it be impertinent,” he said, coolly regarding her, “whether you slowed at all at the corner?”

She bit her lip and stared back at him, a humorous twinkle leaping into her eyes. “If I did not owe you my gratitude, such an inquiry would be impertinent, as you well know, but as you have earned, through your usefulness, a certain right, I will own to you that I was in a hurry, and made poor work of the turning.”

Further annoyed by her sudden levity, Sir Joshua said baldly, “I am only amazed at your intrepidity, ma’am, for attempting a corner at speed in a wagon, and in such conditions.”

“I fear I must amaze you further, sir, for it was not intrepidity but vice that drove me to it,” she replied, without a trace of penitence. “As we are making confessions, you may as well know that I as much as laid odds with my cook that I could be to the village and back before dinner, and you see how well I am served for my reprehensible conduct.”

This admission, made as it was in complete disregard for the inconvenience she had caused him, should have incensed him, but her playfulness of manner touched something forgotten in him, and he regarded her with wrinkled brow. She was so unlike the females with whom he was used to associate that he was conscious of a desire to know her better, but she had little else to recommend her, and the hour being far advanced, he quickly resolved that if he desired to reach his destination before dark, it would be to his advantage to close the interview.

Bowing to the lady, he said briskly, “It is, no doubt, as you say, ma’am, but I believe we are both eager to be on our way—”

“Pray, do not give me another thought, sir, as you have done your duty and must assuredly have better things to do,” she returned sweetly. “Indeed, when I first took your measure, I doubted whether you should offer your assistance at all.”

Sir Joshua—who considered himself, despite everything, to be a gentleman—was shaken, and took some moments to assimilate this unwelcome picture of himself. His better nature—which, having been roused, refused to go tamely—stifled his immediate tendency to discount her assessment by very helpfully bringing to his mind several points of their interaction which clearly supported it. Bereft of this defense, he was obliged to beg her pardon, which he did in a rather gentler tone than he had been apt to use, and prayed her to allow him the honor of handing her into her vehicle, and to accept his very best wishes for her good health and safety.

The lady lowered her eyes in acknowledgement of his apology, and quietly accepted his assistance, but showed no unwillingness to part ways. With a brief nod to him, she set the cob in motion down the road, and Sir Joshua watched her reflectively for a few moments before returning to his curricle to wipe the mud from his boots with an obliging stick. A strange female indeed, he thought, as he retrieved his reins from the branch and, shaking more thoughts of her from his head, was

soon on his way.

His subdued mood did not survive the discharge of his sister’s errand, for though the roads improved, the directions which he had received from his brother-in-law—who was fast becoming, to Sir Joshua’s mind, the most shatter-brained nincompoop of his relations—were sadly lacking in precision. After twice passing the turning which Lord Cammerby had assured him would be on the south, Sir Joshua should then and there have consigned Amelia’s commission to the devil if he had not, in pure desperation, turned north and thus discovered, nearly hidden by a profusely thriving hedge, the address board for Branwell Cottage.

The sight of the neat house set back from the lane was a balm to the soul of as fastidious a landowner as himself, and it was almost with pleasure that he surveyed the well-kept grounds as his curricle swept up the drive. But as he came to a stop in front of the low steps, and no groom came to greet him, a disturbing premonition crept upon him, which was not put to rout when his knock upon the door, though loud and firm, was unanswered. A frown creased his brow as he stepped back from the porch, darkling thoughts blooming in his mind on the respectability of a lady who did not—or could not—employ a servant to answer the door, and the advisability of his sister’s continuing such an acquaintance.

He had just determined on abandoning his errand, and was composing in his mind a firm recommendation to his misguided sister, when faint strains of singing reached his ears, coming from the direction of the garden on the side of the house. His distaste for this troublesome errand was once more overcome by his strong sense of duty, and he resolutely strode around the corner of the house and onto a stone path, which was overhung by trellised vines and lined with late-blown roses and which, in another lifetime, would have enchanted him. In his present state, his only desire was to rid himself of that blasted letter and be on his way.

Two in the Bush

Two in the Bush